Understanding Joint Commitments

In general, human children and infants seem to be much more interested in cooperation, sharing, and committing themselves to a shared goal and a shared experiential perspectives than other primates. In specific contexts chimpanzees exhibit joint, co-operative, coordinated hunting for small monkeys (Boesch & Boesch 1989), and human-raised enculturated chimpanzees successfully solve co-operative problem-solving tasks in which food could be retrieved only together with a non-competitive, familiar human adult both when it required parallel and complementary roles. When it comes to social games, however, such as one person rolling a ball down and another one catching it with a can (complementary), or making a wooden block jump on a trampoline (parallel), the chimpanzees showed no interested and played with single parts of the game set-up for themselves. 18 to 24 month-old human children on the other hand successfully took part in both the co-operative problem-solving tasks as well as the social games. What is more, in contrast to the chimpanzees the children actively tried to reengage the adult when he ceased doing his part of the co-operative activity in both problem-solving and social contexts. Children thus explicitly displayed skills of shared intentionality by being jointly committed to a shared goal with shared intentions. These skills can also be seen in the manifesting conversational and linguistic skills of children around that time (Tomasello 2003).

Pointing in Human Children and Chimpanzees

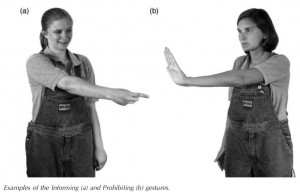

The shared intentionality infrastructure is also already present in communicative power of pantomiming and informative pointing just for the sake of sharing attention and sharing information which infants acquire around their first birthdays (Tomasello 2008: 111). These behaviours even include references to absent object or events such as something that is going on outside, happened in the past or will happen again in the future, a cup that is empty and should be filled, to something that is hidden or not present at the moment (Tomasello 2008: 116f.). Chimpanzee’s on the other hand, practically rarely point in natural contexts, and captive chimpanzees only do so when requesting something, using the human as a “social tool” (Tomasello 2006). A similar imperative behaviour has recently been observed in the wild: during grooming, chimpanzees sometimes point to a specific part of their body where they want to be scratched. (Pika & Mitani 2009). These "directed scratches" however, are also imperative in nature and not declarative.

In contrast, 12 to 18 month-olds also point co-operatively to inform others of the location of an object they are looking for. (Liszkowski et al. 2006 : 173). Generally humans infants and children have a natural tendency to be extremely cooperative in a variety of task and help others solve their problems

“even when the other is a stranger and they receive no benefit at all. However, our nearest primate relatives show some skills and motivations in this direction as well, and this suggests that the common ancestor to chimpanzees and humans already possessed some tendency to help before humans began down their unique path of hypercooperativeness.” (Warneken & Tomasello 2006: 1302 )

The evidence presented here strongly suggest that it indeed seems that social intelligence was a driving factor and the crucial foundation for what makes us unique.

But in addition, it seems that in the human lineage the “Machiavellian Intelligence Hypothesis,”, which sees social competition as the main causal factor for primate, including human brain evolution (Byrne & Whiten 1988, Humphrey 1976), does not apply across the board. Instead, it seems that the unique aspects of human cognition were driven, and are maybe even constituted by, collaboration, cooperation and the natural motivation to share experiences, intentions and perspectives, which then led to the advances in culture, technology, and higher-order cognition we see today (Moll & Tomasello 2007).

References:

Akhtar, N., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (1996). The role of discourse novelty in early word learning. Child Development, 67, 635-45.

Boesch, C. & Boesch, H. (1989): Hunting behavior of wild chimpanzees in the Taï-National Park. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 78(4), 547-573.

Byrne, R. & Whiten, A. (eds) (1988) Machiavellian intelligence: social expertise and the evolution of intellect in monkeys, apes and humans. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

Hare, Brian, and Michael Tomasello. (2005). Human-like social skills in dogs? Trends in Cognitive Science, 9, 439-444.

Herrmann, Esther. & Michael Tomasello, (2006). Apes' and children's understanding of cooperative and competitive motives in a communicative situation. Developmental Science, 9, 518-529

Humphrey, N. (1976) The social function of intellect. In Growing points in ethology (eds P. P. G. Bateson & R. A. Hinde), pp. 303–317. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hurford, James M. (2007): The Origins of Meaning: Language in the Light of Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson (1995): Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Second Edition. Malden et al.: Blackwell.

Miller, Earl K., David J. Freedman and Jonathan D. Wallis (2002.) “The Prefrontal Cortex: Categories, Concepts and Cognition.” In: Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 357: 1123–1136

Moll, Henrike and Michael Tomasello (2006): Level 1 Perspective-Taking at 24 Months of Age. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 24, 603–613

Liszkowski, U., Carpenter, M., Striano, T., & Tomasello, M. (2006). Twelve- and 18-month-olds point to provide information for others. Journal of Cognition and Development 7: 173-187.

Moll, Henrike, & Michael Tomasello. (2007) Co-operation and human cognition: The Vygotskian intelligence hypothesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 362: 639-648.

Moll, Henrike., Richter, N., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2008). Fourteen-month-olds know what ‘we’ have shared in a special way. Infancy, 13(1), 90-101

Tomasello, Michael (2003): Constructing A Language. A Usage-Based Approach. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, Michael (2008): The Origins of Human Communication. Cambridge, MA; London, England: MIT Press.

Tomasello, Michael and Malinda Carpenter (2007): “Shared Intentionality.” In: Developmental Science 10.1, 121-125.

Tomasello, Michael, Malinda Carpenter, Josep Call, Tanya Behne, and Henrike Moll (2005): Understanding and Sharing Intentions: The Origins of Cultural Cognition. In: Behavioral and Brain Sciences 28:5, 675–691.

Warneken, Felix. & Michael Tomasello, (2006). Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science, 31, 1301 - 1303.